This week, Battleaxe is leaving this dreadful present behind and retreating to her rural past. Recently… (when…all the weeks run together) on a walk round Winchelsea, we met a young farmer moving his newly-sheared sheep from one field to another. This struck a memory chord… and you’ve even got a poem. Battleaxe was brought up in the country, usually miles from anywhere, because her mother’s dogs were a massive neighbour nuisance.

Rural past? We’d seen those same sheep before. ‘Those ewes need shearing and dagging’, I’d fulminated to an unimpressed Philosopher. (For those without a rural past, ‘dagging’ is cutting off the dung-stained wool from around sheep’s bums to prevent grisly ‘fly-strike’ in hot weather).

Neighbour nuisance? I’ve mentioned before that my mother bred, showed and judged dachshunds – we had up to 40 of the noisy horrors. In addition, my parents were a rackety pair – constantly on the move, either escaping something or someone, or finding a new project.

When I was about 10 they moved to South Weston, a little village on the fringe of the Chiltern Hills. Today, the M40 passes nearby, but in the early sixties it was very isolated. The four years we lived there spanned my transition from childhood to adolescence.

Our house was at the top of the village, opposite the church, with over an acre of over-grown garden. Plenty of room for the dogs, but nothing for a solitary child with parents who took very little interest in her.

However, to my own surprise I found a friend, Mary, the daughter of a bohemian and even more rackety pair of stained-glass makers who lived nearby. My mother thought Mary was common, cheeky and ‘knowing’ and didn’t like her in our house. That was OK with me because I was scarcely ever at home. When I wasn’t at school, I’d leave the house early in the morning and not return until supper time.

Manor Farm, at the other end of the village, was our play base.

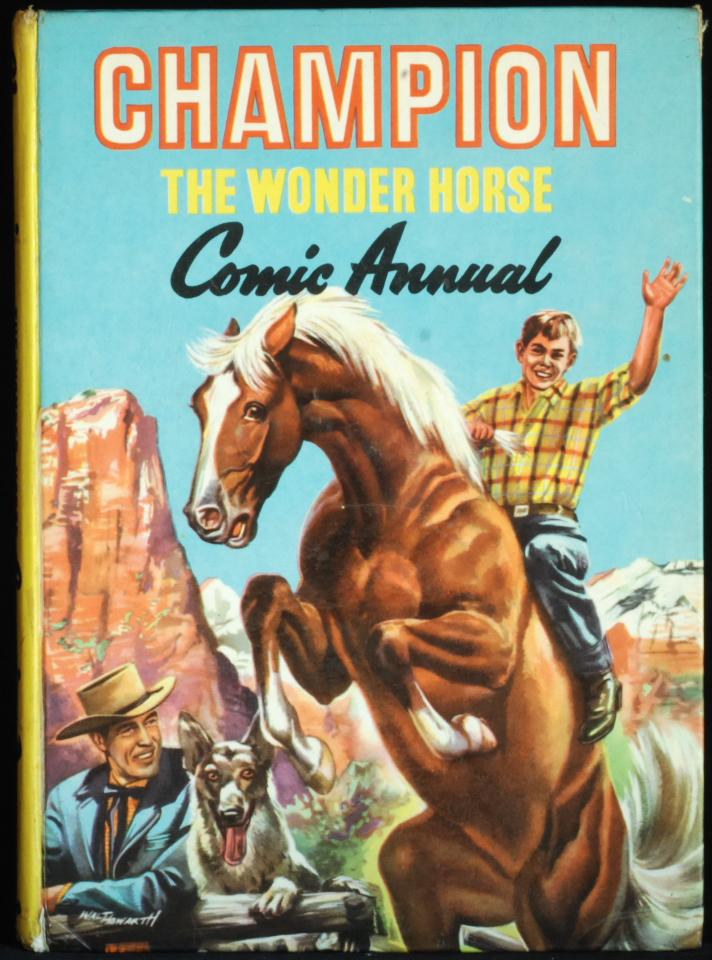

The farmer’s wife, Mrs Keen, let us use an abandoned, dilapidated shed in the middle of a field as our ‘ranch’ – our obsessions then were ponies and cowboys. The Keens had one son, Charles, much older than us, of whom more later. Mr Keen was not quite so fond of us, and often put mischevious bullocks in ‘our’ field. However, Mary and I were not afraid of the beasts, who, curious, would gather round the shed when we were inside. To get out, we’d fling the door open and shout ‘Yee-haw’ waving our arms to scatter them. Just right for us cowboys… Back then, there were all those Westerns on the telly – Rawhide, Bonanza, Wagon Train… and best of all, Champion the Wonder Horse. Ricky, Rebel, Uncle Sandy…

At times our two became three, with the addition of Dennis, a Barnado’s boy from London who spent his summers at the Vicarage. The Vicar introduced us, and my snobbish mother must have had a total nervous collapse. But nobody dared upset the Vicar… he’d been in a prison camp in Singapore, and was Delicate. Poor Dennis, we bullied him rotten, even though he thought himself very tough. We were two sharp-elbowed, sharp-tongued little tomboys, bristling with cap guns and swiss army knives. He was a big, slow lad, terrified of all animals, even the Vicar’s two donkeys, which Mary and I minded, taking them up to the churchyard each day to graze the long grass.

Mary and I wanted to ‘help’ with all aspects of farm life. Farms are dangerous places, and we had to watch out for Mr Keen. He patrolled his empire dressed in tweeds, carrying a stick. On several occasions that stick caught us painfully round the bare legs when he caught us playing in the wrong places, or interfering with the men’s work. But it didn’t stop us…

One dreadful day we were playing by the grain drier, climbing the ladder to the top of its tall shed, and edging round the narrow walkway above the big silo that held the grain. Mary fell down into the silo. The grain was like quicksand, and the sides of the silo were smooth. From above, I looked down at her as she cried with terror. I knew that I must hurry to get help, or else she would sink below the surface… but I was terrified of Mr Keen. Reader, I hesitated, weighed up the options. Thank goodness, I made the right choice, and fetched one of the men. We got in huge trouble. Our parents were told, and we were banned from the farm for months. But I will never forget the knowledge that I was capable of that hesitation, that weighing-up… I don’t think Mary ever knew.

Time moved on, and the Keen’s son Charles was home from agricultural college. He must have been about 20, tall, loud and blond, very much the Tory landowner in the making, and meanwhile, Mary and I were getting older. She was sent to a boarding convent in Maidenhead, and aged 12, I had started boarding school in Oxford. I’ll put a poem in here… taken from Battleaxe’s 2019 collection ‘Lines and Wrinkles’.

Harvest Time

I’m running to the gate

in the last light of endless summer,

pulled by a distant grumbling roar.

Combine harvester, heading homewards to the farm.

How old am I? Eleven? Twelve?

Still unformed, sexless in Aertex shirt,

scabbed knees in khaki shorts.

Time ran freely then, spooling past in random snippets

of building dens, Champion the Wonder Horse, Tizer,

dead rabbits in the woods, and, at harvest time,

the huge red combine, edging down the lane.

Spiky rollers whip brambles from the verge,

long-necked chutes like dinosaur heads

graze the overhanging trees.

Hot engine breath sears my legs,

the ground trembles.

There’s Charles, the farmer’s son. He’s old enough

to drive the thing, yet still a shouty, mocking boy.

I don’t like him, but this time, as he waves,

mouthing insults I can’t hear,

I see him.

I see the little hairs on his forearms

shining gold in the setting sun.

I can’t wave back

my mouth’s gone dry.

He shifts the machine into a different gear.

I hope he’ll turn, look at me again.

He doesn’t.

Indoors, they’re at the table,

dogs round their feet.

I take my napkin from its ring.

‘Who was driving?’

‘Charles’ I reply, blushing

Well, needless to say I spent the next I don’t know how long trying to catch glimpses of Charles. He, of course, was totally oblivious. For me, it set up a fatal attraction for farmers – of which more in a future episode of memory nostalgia…

Good to hear from you, Battleaxe. What an interesting description of part of your personal history!

Author

Thanks Judith! It makes a change from writing about the horrors of the pandemic!

Brilliant evocative piece! You really catch the freedom and challenges of childhood, growing up and the class system. I love your poem Steph.

Author

Hi Keith – nice to catch you on here! Glad you enjoyed the piece and the poem, hope all is well with you and yours.